Trust is an elusive phenomenon. It is a fluctuating relationship that needs to be nurtured to secure the pillars on which the credibility of institutions, the legitimacy of institutions, the ability to delegate and social cohesion are built. It is a volatile manifestation of expectation management that has become even more fragile in the digital society.

In 2020, trust in public institutions experienced a significant increase over previous years globally. For the first time in decades, citizens considered their governments to be the most trusted actors at a time when they were looking for guidance and solutions in the fight against Covid-19. This growth was even linked to more effective management of the pandemic, as countries with higher levels of social and governmental trust saw a slower spread of the virus and a lower mortality rate. However, this change in trend was only a transitory event. Six months later, trust in public institutions had fallen by 8 points globally compared to the 2020 results.

In Europe, the situation is particularly striking. According to the European Council on Foreign Relations, European citizens had less confidence in the bloc’s institutions a year and a half after the start of the health emergency. This is because the aspirations they had harboured for a better and more effective European cooperation at the beginning of the pandemic had not been fulfilled.

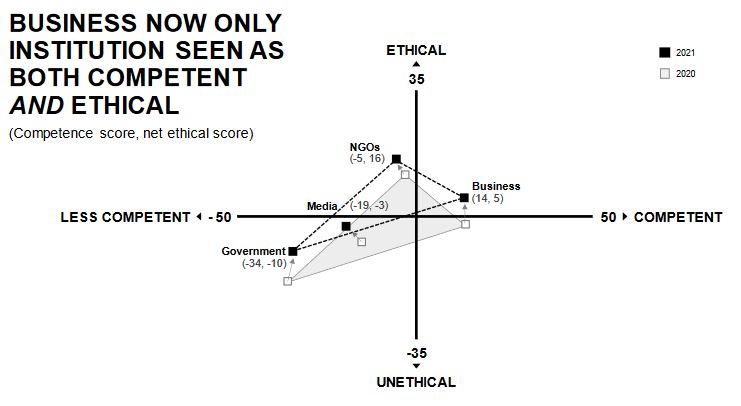

In this scenario of decline, business is the counterpoint. Companies have managed to position themselves as the only trusted entity (with 61 points) ahead of NGOs (57 points), governments (53 points) and the media (51 points) in 2021. Business are also the only one of these agents considered by citizens as competent and ethical.

(Source: Edelman Trust Eurobarometer, 2021. Global report)

The keys: competence and values

These two indicators (competence and ethics) are closely related to the OECD’s key factors for building trust in governments, namely competence and values. However, both criteria are also perfectly applicable to other types of entities, such as companies.

Trust in competence refers to the ability to deliver, to implement what is promised and established, and is generated when institutions provide useful services to people. In this sense, their capacity to offer a real (and anticipated) response to citizens’ needs and reliability in the management of these services are pivotal, as demonstrated during the Covid-19 crisis.

Trust in values is the result of integrity, fairness and openness. Integrity is about using power and resources ethically, while fairness is about improving the living conditions of all people. To complete the triad, openness is based on the ability to listen, consult, and compromise with different stakeholders.

On the basis of openness and participation, collaboration between different actors is particularly important to mitigate some of the most relevant current risks that are undermining levels of trust in the digital society. These include security in the utilisation of digital services, the ethical and open use of Artificial Intelligence and data, and disinformation.

Security in the use of digital services

The pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital services, from the popularisation of remote working, to the increase in online shopping or the online management of a large number of procedures. For citizens to use these services, they need to be able to trust them. People need to feel safe when using digital tools and systems, and it is therefore essential to address the growing cybersecurity threats.

Around one in three consumers has been a victim of cybercrime in the last year. Despite the fact that many users claim to be more cautious when surfing the Internet, around 2 in 5 feel more vulnerable to cyberattacks than before the pandemic.

This is a cross-cutting problem that needs cooperative solutions. No single state or company can tackle global cyber security threats alone. It is crucial to incorporate a holistic view of digital security that covers the full cycle of prevention, detection and response. In this way, public institutions and the private sector must actively collaborate to reduce the risk of threats. In addition to this, a culture of cyber resilience and cyber resistance must be fostered in order to raise awareness of digital security and help reduce the number of breaches.

Ethical and open use of Artificial Intelligence and data

Artificial intelligence and data have shown great potential to solve the most pressing social and economic challenges. Examples of these possibilities include initiatives to reduce pollution, optimise traffic management or, more recently, improve the evolution of Covid-19 infections. The use of aggregated and anonymised data from mobile network operators to fight Covid-19 has been highly efficient in controlling and combating the virus. This is the case of initiatives such as the Scenario Analysis Toolbox to simulate infection scenarios by manipulating variables or the public-private partnership between the European Commission and 17 mobile network operators to understand the correlation between mobility and infections.

In the interest of leveraging the benefits of AI and data while reducing potential risks, it is essential that the uses we make of this technology respect fundamental and enshrined rights, such as privacy. Public institutions and companies employing these services must implement existing best practices to ensure that their use is responsible and builds users’ trust. To achieve this, individuals need to be able to manage and control their data. They must also be able to make granular choices and avoid all-or-nothing options. A relationship based on trust is the basis for a healthy model of fair data exchange from which all parties involved can benefit.

Disinformation and manipulation of the public sphere of opinion

The rise of fake news and manipulated information has contributed to increased distrust of government institutions, processes and systems. Disinformation has the capacity to polarise debates, create or deepen tensions in society or influence electoral processes, while potentially undermining freedom of opinion and expression. Telefónica’s Digital Deal lists a number of recommendations to address this phenomenon from a global perspective. Firstly, we need to define the role and responsibility of each actor in the internet value chain for this type of content, as well as the balance and interaction between them. The psychological, cognitive and formative predisposition of individuals to receive and share this type of material makes it essential to promote digital literacy programmes and active communication campaigns. This will facilitate access, recognition and availability of truthful and fact-checked information. This battle requires a collaborative system based on a triple alliance between public institutions, businesses, and citizens.

The seed of a new relationship of trust between the different actors and the digital society must be based on values, competence, and collaboration, in that order. For the necessary cooperation between different stakeholders, each actor must first be competent to deliver on what has been agreed and on the individual and collective commitments made. For these agreements to be sustainable, they must be based on values, including transparency, integrity, and accountability.