Technology, education, adolescents. A complex mix. Often demonised and often demonised. And of mixed feelings, following the recent PISA report that reveals gaps, not to say dangerous shortcomings in our compulsory education system.

Innovation

We often talk about innovation, although it does not mean the same thing as progress. It is true, sometimes there are unfortunate misalignments. We have sharp insights like the one Byung-Chul Han shows us where he explains a potential breakdown of today’s world: “We perceive reality through the screen. The digital window dilutes reality into information, which we then record,” he says. We consider aspects that take over and dominate us: the lack of our young people’s capacity for analysis and concentration. The lack of comprehension and a low reading intensity. Probably due to a hasty introduction of screens (a bad use and misunderstanding of technology by parents) and the consequent bad habits and foundations towards reading and writing, especially in the 0 to 6 years stage. We have children with feet of clay.

But now I want to turn the reasoning on its head, because the opposite would not help us either. There is talk of banning mobile phones for children under 16. There is talk of technophobia or even an example of certain currents in supposedly more “advanced” countries that have decided to completely eliminate technology from their classrooms, a kind of return to arcadia.

But let’s be honest: according to the INE, 7 out of 10 schoolchildren between 10 and 15 years old have a mobile phone at the age of 13, and at the age of 13, the percentage reaches 94%. According to the latest UNESCO GEM report, since 2010, the amount of time teenagers spend online has doubled. And the question is not so much how much time… but on what or for what purpose. And I believe that young people need to be accompanied, considering their maturity, so that their screen time does not turn into passive consumption, into a destruction of life by attending to stupidities. And in the classroom? In Galicia, Castile-La Mancha and Madrid it is prohibited, although the school is delegated the power to decide its use for pedagogical purposes. Some experts recommend prohibiting their discretionary or recreational use at school, although without limiting the development of their technological skills. And the truth is that the authors of the PISA report themselves advocate not banning phones in the classroom. Perhaps because, although we are told otherwise, screens do not isolate, in the words of Laura Cano, professor at UCJC. Young people use technology to relate to each other, to assert themselves. Or if you want to speak more strictly or scientifically, according to a study in a sample of almost 8,000 validated participants, screens do not damage the brains of adolescents.

And the answer I think (and this is my own) would be to educate, to set limits, to talk to your children about how they use technology and what it does for them in their learning and their daily lives.

Incorporating technology in the classroom

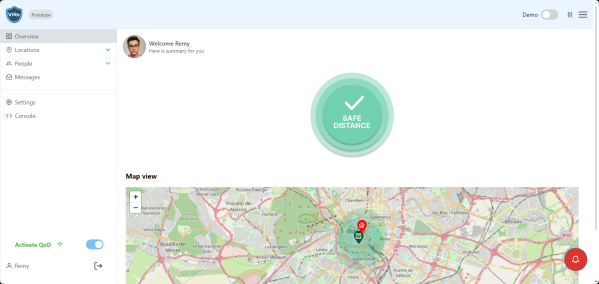

Now let’s take it a step further. Let’s talk about incorporating technologies in the classroom or boosting the STEM curriculum along with the softer skills. I am concerned about the former, as I consider the latter to be mandatory. In this sense, we already have a series of very transversal technologies such as platforms and applications that speed up the delivery of material and student collaboration. All our children already use them and it would be a huge step backwards to limit or eliminate them. We need to expand, we need to expand these channels of communication and work on enriching the learning experience. Virtual reality experiencies come to mind, where we have been working at Telefónica and where, for example, we found relevant uses in terms of presenting architectures or better understanding how our bodies work. Much has also been said about educational robotics to encourage our students’ creativity and thus train their programming skills: I can’t imagine a job in the future that doesn’t use code in some way. But certainly the biggest uncertainty at the moment, and certainly the biggest growth area, comes from AI, especially generative AI. Close our eyes and let the train crush our children? Not at all!

I recommend visiting enlighteED and getting informed, especially with those talks that are more applied, such as the one by science populariser Carlos Santana, in order to understand its potential uses in the classroom. Examples: when he explains that generative AI will be a kind of small full-time teacher with new study and self-assessment dynamics that are much more personalised and directed. And let’s not kid ourselves, if our son says he hasn’t used it yet… he’s lying. Let’s sit down with him and practice, because the magic of generative AI lies in knowing how to ask it and I predict here a paradigm shift: our old encyclopaedic knowledge search scheme (I am a child of the 20th century) that turned into the search engine filter model (first and second decade of the 21st century), will surely be transformed into knowing how to ask to get the best answer. And I love this Socratic touch towards which we are heading! Because to ask questions you have to have a good base of culture and knowledge.

In conclusion, I am a radical optimist (not uninformed) and I believe that technology, especially when applied in the classroom, is mainly a source of solutions and progress. Of course there are shadows. We cannot allow anyone to be left “behind” or to be thrown into an absurd race of consumption and purchase of useless devices. I believe that clinging to hackneyed stereotypes (we used to be better) does not help. Let’s apply critical analysis and allow our children to grow up with these new skills and tools at their fingertips. For me this is called full education.