2023: Departure for the Digital Decade

Just five days ahead of Christmas 2022, the Policy Programme for the Digital Decade was published. After 15 months of discussions, the institutions for the first time explicitly agreed a digital policy framework for the EU.

2023 thus marks the year of programme take-off. Of course, labelling the proposal as the ‘path to the digital decade’ suggests a singular quality for this decade unlike any other before it – yet the EU and its Member States have been on a digital trajectory since at least 2010 already. Then, it was the Digital Agenda for Europe that outlined a vision for digital transformation by 2020.

So, what does the Union’s new digital decade look like?

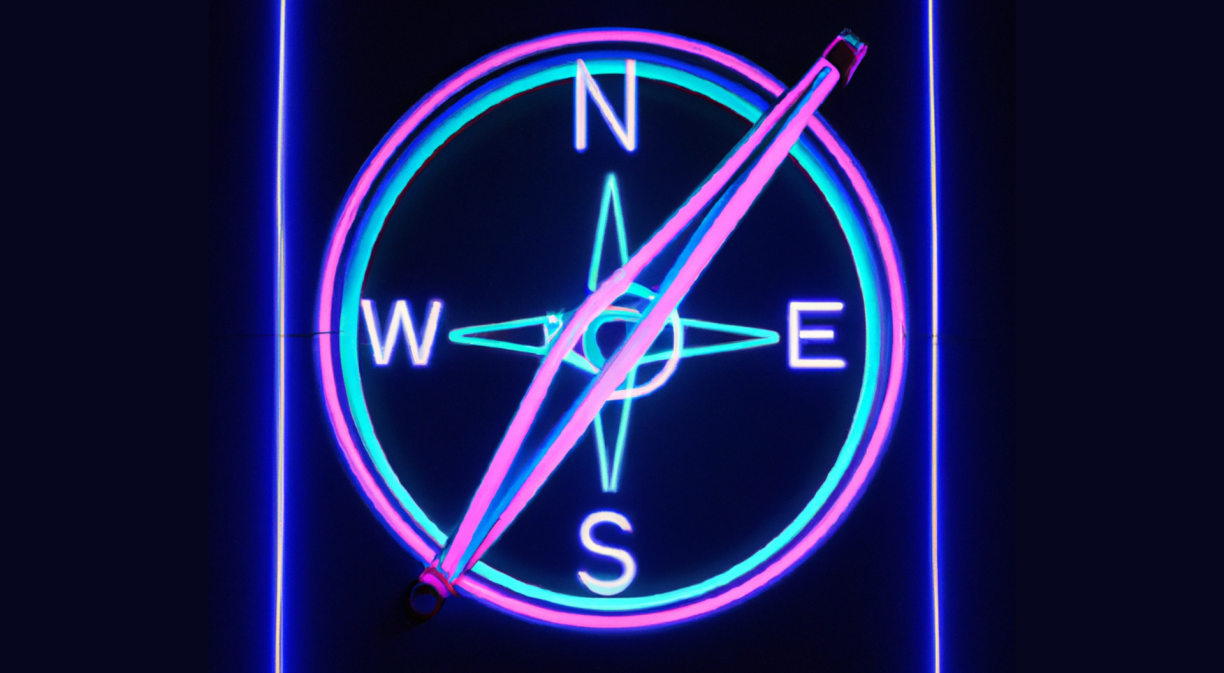

One of the most widely shared illustrations of what the Policy Programme sets out to achieve has been the following:

Skills, infrastructure, business and government were presented as the ‘cardinal points’ when the idea of a programme was first outlined in March 2021. Today, the adopted programme acknowledges them as the essential areas for the digital transformation of the Union.

The Digital Compass attaching measurable targets to each of these areas was approved by the Member States when they asked the Commission to convert the idea of a policy programme into a legislative proposal. Consequently, the targets have remained substantially unchanged until adoption.

The magnetic North of the Digital Decade: Where are we headed?

The attractiveness of the compass resides in its familiarity. Most, if not all, people will recognise the visual outline of a compass rose and associate with it a sense of orientation.

Built into the compass is the shared understanding that, despite its even-handed form, only one of the four cardinal directions (as they are commonly called by compass makers) provides reliable bearing. While this direction does not predetermine the path to be taken, failure to orient one’s path against it will inevitably lead one astray.

That direction, of course, is the magnetic North, based on the Earth’s magnetic field. In the Digital Compass, the European Commission elected, and the co-legislators endorsed, ‘Skills’ as the magnetic North of EU digital transformation.

While, at first sight, this choice appears a natural fit with an approach to the digital decade that is human-centred, it is less clear that a focus on skills can provide the principal orientation required on Europe’s way towards 2030.

To see why, it is worthwhile recalling that the four cardinal points themselves originally were split into two dimensions. Skills, together with infrastructures, constituted the dimension of digital capacities.

The building of such capacities has constituted an overarching political objective of the Commission President and her Commission since 2020. Then, in her first State of the Union address, Ursula von der Leyen first insisted on making this Europe’s Digital Decade, with an emphasis on the fields of data, technology and infrastructure. All of these, and specifically the conception of a more coherent European approach to connectivity and digital infrastructure deployment, constitute strategic components of Europe’s digital sovereignty.

The digital targets relating to infrastructure precisely reflect this understanding by defining objectives that are not only ambitious for the Union itself, but also seek to position it in a leading position internationally. This is evident not only from the explicit intermediate goal of establishing the first EU quantum computer by 2025, but also by aiming to provide Gigabit connectivity as well as 5G or better mobile access everywhere where people live and work.

But other than simply being aspirational, these infrastructure targets are also foundational: without the achievements that they anticipate, the digital transformation of business and public services, but also the development of relevant skills are unlikely to be achieved. This is particularly true for the target of ensuring connectivity of very high quality for all Europeans.

Indeed, what infrastructure is to the Digital Compass overall, connectivity is to its infrastructure dimension: for without the necessary links to facilitate digital interaction and exchange that is swift, stable and secure, even locally successful digitization efforts are doomed to remain outside the Digital Single Market and thus limited in their ability to contribute to, and benefit from, EU digital sovereignty.

Hence, without detracting from the importance of skills as a critical capacity to build on the way towards 2030, infrastructure defines the magnetic North of the Digital Compass that will provide the principal orientation on the EU’s path to 2030.

True North: Ultimate orientation for the

EU´s digital efforts in more than numbers

The picturesque analogy of a compass to guide Europe’s digitization efforts would not be complete without touching on an issue well known to explorers, navigators and those otherwise interested in the correct functioning of compasses in real life.

While the magnetic North provides orientation based on alignment with the Earth’s magnetic field, that mechanism becomes increasingly unreliable as one approaches the North pole: with increasing vertical pull on the compass’ needle, navigation becomes more and more difficult, to the point of the compass losing its usefulness.

To account for this magnetic variation, true North designates the direction towards the point at which the imagined rotational axis of the Earth intersects with its surface – independent of changes in terrestrial magnetism.

For the Digital Decade, it may appear tempting to define its true North in a similar fashion by setting a hard and fast target to lock in specific ’coordinates’ at which the EU should arrive by 2030.

Yet this would be to ignore that the final destination to orient the voyage of EU digitization is not – and cannot be – given by a however ambitious, quantifiable target. While such a measure can help to assess progress, the destination itself must be found in another plane.

The legislature has established this through a set of general objectives beyond the digital targets, as shown below.

The guidance function of these objectives is immeasurably important, as they define the human face of digitization beyond technical performance achievements alone. For the first time, the institutions have made a joint commitment to situate digital policy in a wider set of normative coordinates. The vision emerging from this echoes many of our company’s beliefs about the power of connections.

We welcome the boldness to dream big and thereby provide a clear direction for the EU’s digital transformation. As the very first sentences of the Policy Programme recall:

The Union’s path to the digital transformation of the economy and society should encompass digital sovereignty in an open manner, respect for fundamental rights, the rule of law and democracy, inclusion, accessibility, equality, sustainability, resilience, security, improving quality of life, the availability of services and respect for citizens’ rights and aspirations. It should contribute to a dynamic, resource-efficient, and fair economy and society in the Union.

Digital, connected,… fair?

Looking to the future and the road ahead, a key question is how far the European Union wants to go, and how far it is able to go, in furthering a fair economy and society, as the Programme is being implemented.

This is a question that reaches significantly beyond the digital targets in isolation. Importantly, the legislative process added to the Commission proposal a particularly salient general objective. By that objective, the EU institutions and Member States are to pursue

a Union digital regulatory environment to support the ability of Union undertakings, especially that of SMEs, to compete fairly along global value chains.

Without a doubt, the impact of digitization on SMEs is critical, for the lack of access to digital capacities, and especially of connectivity to showcase their activities to the world, may previously also have played a shielding role. As experiences in retail, artificial intelligence and fashion show, digitization can foster cut-throat competition that threatens European SMEs’ ability to survive in a marketplace where price and convenience dominate.

Maintaining the ability to compete fairly in global supply chains concerns all of the EU’s industrial base. This dimension of the digital EU’s true North is cross-cutting. The European commitment to ensure that all those benefitting from the digital transformation make a fair contribution to the public infrastructures, goods and services underpinning it, therefore serves as a reminder of the preconditions of fair competition.

Special power comes with special responsibility – whether for companies or policymakers. EU institutions and Member States now need to take on their responsibility. For if fairness is absent from the infrastructure of the digital value chain itself, it is not clear that even achieving the digital targets can produce a fair outcome for Europe’s economy and society.

To realize this will be essential to driving the connectivity sector’s own digital transformation that Commissioner Breton sees under way and to which we and our peers are relentlessly contributing. Failure to do so may let the giant leap ahead of us come up short.